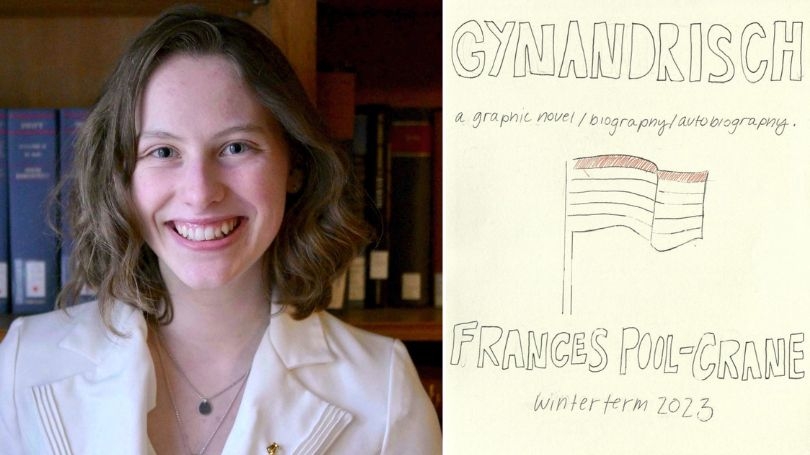

As her culminating German studies project, Frances Pool-Crane '23 wrote a graphic novel that reflects on kinship with lesbian women and gender nonconforming people in the Weimar Republic.

After learning German during the pandemic with no time overseas, German studies and English major Frances Pool-Crane '23 wrote a graphic novel that reflects on finding historical kinship with lesbian women and gender nonconforming people in the Weimar Republic.

Pool-Crane, who plans to attend Cambridge University and pursue an MPhil in English, spoke with German studies professor and department chair Yuliya Komska about her interest in queer studies, finding research inspiration while looking for outfits on the internet, the difficulty for rendering humor in another language, wanting to translate more, and her ambition to make up "believable" German words.

Yuliya Komska: Let's start from the beginning. Why German?

Frances Poole-Crane: When I came to Dartmouth, I knew I wanted to learn a new language, but I didn't quite know which one to take. I had done Spanish in school up till then, and I went to a German open house during orientation – everyone was so nice and enthusiastic, and I thought – Okay, I'll take German.

An accident! But a happy one?

Yeah, I'm happy about it! I liked it enough to major in it.

You learned German entirely in a pandemic without ever going abroad. What were the challenges of that and what were the benefits?

It is tough, because I do see that people who have gone abroad are often way more confident in their speaking, in a way that is a lot harder to achieve when it's all been in a more controlled classroom environment, and especially in an online classroom environment. But I was lucky enough that I had the very beginning of German in-person. I took German 2 in-person, and I think that was really important. And I had all of my advanced German classes in person as well. Just having those bookends was enough to make me pretty confident in my abilities.

Your spoken German is amazing. What would you like to be able to do in or with the language in the future?

I'd love to do more translation. It's always really appealed to me as an aspirational thing because it's so hard. I did it in the first upper-level German class that I took, where we had a little tiny translation assignment, from German to English. I think it was a Heinrich Heine poem. And I just had so much fun with that, that it's just been in the back of my head since then that I would love to do more translation. I don't really know of what yet – I just think the practice is really exciting, and I'm excited to be at a level where I'm able to do that.

In your mind, what can German do that English cannot? Because you're also an English major, and you're very close to not just living in the language, but also feeling in it and thinking about it. Does something come to mind, either a specific occurrence or an experience or the process of phrasing or writing something?

Yeah, that's a good question, because I do feel the difference very intensely, and I felt like one of the first things that happened when I did start feeling like I knew German pretty well, was that I thought a lot more about English, too, because it stopped being the only language that existed for me, and started being something that I felt like I was choosing.

This is a standard answer, but the compound words are fun. It's a skill that I'm not super confident in – being able to make up believable compound words. But it feels good to try to put them together. I think there's an element of creativity there and thinking about connections between things that you don't have to do in English – or don't get to do in English – in the same way.

Do you relate to German words and thoughts in German in a way that feels different from other languages?

I've wondered a lot about my personality in German, if it's different at all.

What have you noticed, if anything?

I still don't quite know how to be funny in German, which is difficult because I think I am in English. Humor is a facet of my personality that I feel is so much harder to highlight when I speak German, because I'm still concerned that it doesn't translate well. I think humor is hard to translate, so I feel like I have to start from scratch a little bit in German, which is an exciting opportunity, and also one of the things that I feel like has come last in language learning. I couldn't, just a year or two ago, have been able to maybe even know what was funny in German.

Speaking of the sense of humor, you wrote your culminating project in German in a way that was very personal and also very funny. Could you just describe in a few words what it is or what you set out to do with it and what it did for you?

The project became a lot bigger than I had expected it to be at the start. At the start I wanted it to be a historical narrative. I just wanted to tell the story of the women whom I had found through research, and then the research process itself became so much bigger than I had expected, not even just in volume, but sort of just emotionally bigger, because volume wise, there isn't that much. But just the experience of finding it was as rewarding as what I ended up finding.

Describe it in a nutshell, would you?

It's a short graphic novel about my process of researching the lives of the photographer Marianne Breslauer and the writer Annemarie Schwarzenbach. Schwarzenbach was a very androgynous, mysterious Swiss writer, and Marianne Breslauer was a photographer who did a lot of portraits of her and of other gender non-conforming or lesbian women in the 1920s and thirties in the German-speaking world. And so my project is telling the story of my research about these two women's lives and what that meant for me in terms of getting a sense of historical belonging, in learning about the history of gender non-conforming people and about gay and lesbian history, and facets of it that feel new.

And why did you choose graphic novel as form?

For one, I thought it would be a fun challenge. I don't have significant experience, or any training, doing illustrations or drawings, and I don't consider myself particularly artistically talented. But I am still very interested in telling stories through visuals. And I also love comics. I especially love the comic strip Dykes to Watch out For, and in general, the lesbian comics of the nineties and early 2000s. It's a very interesting tradition, with how rich it is. I think a lot of people don't know the extent of how huge specifically lesbian cartoons, and lesbian cartoonists, were and are. And I wanted to sort of throw my hat into that a little bit and see how it went, because it wasn't the highest stakes of project, so I felt like I could do something more unexpected that I hadn't done before, and I had a lot of fun with it.

And what does your book bring to that tradition?

I think it brings together some different facets that may have not been put together before in this form, like how I handle history, not looking at just a specifically personal story while also not dealing with fiction. I think I'm telling a story that is very personal to myself, in one sense but is also quite universal. Wanting a sense of belonging within history, or to see yourself in history, is a very, I think, universal desire. We want to know about stories of people like ourselves who have lived before us and who have lived exciting and interesting lives, despite things that might have made that difficult, especially at the point in history that I was researching. I don't think my story, on its own, brings anything revolutionary to the table. I think it's just another perspective of which there should be more.

The book operates on two levels, the personal and the historical. Tell us how easy or difficult it was to put yourself out there in visual form, or to make your very interior and innermost thoughts public. And then it would be great if you could speak about how you went about researching the historical facets.

The personal part is always going to be a little bit mortifying, no matter what. I feel like putting yourself out there in any artistic form is so scary, it's like saying, 'Oh, I made this, and I think it's good.' I knew that by choosing a medium like this, there was going to be an element of that mortification. Adding more of a deeply personal element, to me, felt like, well, I'm already embarrassing myself by making this, so I might as well take it all the way. I care a lot about this, and I care a lot about telling the story. And I thought that people would care more about it if I show why I felt it to be such an important story to tell. I think that is it. It's one thing to say: this happened in history. It's another thing to funnel that history through oneself.

As for the research process, I came upon the story – the story that's inside of the graphic novel – initially through this article that was called something like "15 gorgeous portraits of 1930s tomboys". And I looked at that article and more than a half of the portraits in it were of Annemarie Schwarzenbach. And I thought, "Who's this? This is interesting. This is not what pictures of women from the 1930s usually look like." And after that point, once I was grounded in a subject, it was just looking at the library catalog, looking at different databases, and scanning newspaper archives. And there were a lot of dead ends in terms of, you know, you see a name mentioned in the newspaper and that doesn't ultimately mean that much, even if it is the right person. I would love to keep on with the research path that I started on there because I'm sure there's so much more. But with the amount of time that I had, I feel like I covered a lot of ground.

It's instructive that this research project, which doubles as a project of personal inquiry and activism, can come out of something seemingly trivial. Perhaps it speaks to the fact that nothing is trivial to a curious eye. Is it fairly typical of how you get inspiration?

That's interesting. I would say no, but I wish it was. And I think it's opened my eyes to where I can find new ways of looking at things and new places to find subjects. I don't think I had ever discovered something that I took this seriously in that way before. My biggest projects in college have generally come from traditional places and practices. I read a novel, and then I care about that novel, and that's what I work with. I had never started something like looking for outfits in my free time. But I'm really interested in visual studies, and I haven't been able to explore that much in some ways, and I feel like this was an amazing way to go down that path in a way I hadn't before. And just using that article as my original source feels like it's opened up a new world of places where I could look for more things to research.

I have so many favorite pages in your novel. Do you have a favorite? And if so, could you describe it and say why?

I have a couple, but one comes to mind right now. I think maybe because one of my first thoughts in this project was about the 'desire-web' in the 1930s German-speaking lesbian world. Once I really got into the nitty-gritty of the research, and I saw all these metaphorical lines connecting Schwarzenbach to different women with whom she had affairs. And I was thinking about this web of people who were all interconnected at the time. There's a page of the book where I draw her web, and then I draw a fictionalized web of how that same idea exists at Dartmouth. The lesbian web here is a topic that comes up so much when talking with friends, talking about how, when you have a small community here, it's going to be these complicated lines of connection between different people. And honestly, that was one of the most intense points of historical identification that I wanted to highlight in the novel. The fact that the nature of our community maybe hasn't changed that much in almost 100 years, at least in a place like this. I think that's probably one of my favorite pages. It's not the one that was visually the hardest to make, or even really the most interesting. But thematically, it involves some humor, which I wanted to keep at the forefront, while also still being a serious point of identification that I wanted to highlight.

And you presented the book in the winter term, the response was terrific. Could you maybe say a few words about if you've shared parts of the book, or all of the book, with other people? It's written in English, so a lot of people can read it. What were their reactions like?

I shared a draft of it with one of my friends here before I first turned it in, and because the two of us have a lot in common in terms of feeling this historical alienation, she found it very sweet, I think. Outside the presentation, I have shared it mostly with my friends and people who I think will relate to it, which is not necessarily the intended audience, but definitely generates more emotional reactions. It's a secondary kind of identification, because it's a story about historical identification. When you show it to someone who's had the same experiences as you, that person can find a level of interpersonal identification even if they haven't heard of the subjects. The book speaks to them, too, which is my goal overall. It feels especially meaningful when I show it to other women on campus or other lesbians on campus that have experiences similar to mine.

And what has it meant to you that a kind of historical kinship emerges with remote people in a country that's not Anglophone? Through your research and personal interests, you've known a lot about queer culture in the UK. What has discovering this material for yourself in Germany meant to you?

It's been really interesting. Even before I knew much German, I was already hearing about the Weimar Twenties and thirties as this unexplored (for me) gay capital. And I had been almost afraid to touch that in my research, with the way it was so mythicized in my head. It was wild to realize how different life was for a gay person in the Weimar Republic, compared to the life of someone from England at the time. And the linguistic and geographic difference does definitely give my project a further sense of removal from my own life. Especially in the fact that the book is in English, but all of my sources were in German. But I think it also highlights something about universality there, about how, obviously, we're historically removed, and geographically removed, and linguistically removed, and yet there's still this intense identification.

If you were to dream about the future of this project, where can you imagine it going?

I would love for it to have a life beyond what it is right now. I don't really know how, because I'll have to find out how much more there is that I can learn about it. But I would love to just keep on going with their story, to make it more detailed, delve more into the specifics of their lives and the further personal connections that might be there. With more research, it feels like there's a natural continuation of this story that I would really love to explore further. I think it could turn into something a lot bigger than what it is now and something that remains worth telling.

That sounds great. And sadly, you're graduating – what's next for you?

Well, next year I'm going to do an MPhil in English Studies at Cambridge. So I'm moving. After that, I would hopefully like to do a PhD — so I'll be applying to those. Just in the past year, I feel like I've found myself in some topics and concepts that I feel like I want to stick with for a long time. I'm sure I'm going to reach some dead ends at some point, but for now, there's so much I'm so excited to explore, and a lot of ideas that I've been thinking about that I intend to keep thinking about. That definitely became clearer to me through this project – something that I've thought about a lot, that I would love to keep thinking about, is, specifically, the figure of the lesbian artist, in fiction and in life, and what that figure represents beyond just the individual. This project, along with my undergraduate thesis and previous research, has really made it clear that I want to stay with that idea longer and really develop it further. And I would love to think about that in a more geographically and chronologically diverse way.

And do you see German being part of that?

Definitely. Like I said, I'd love to do more translation. I can sense that there are lots of points where it'll be especially important to make transatlantic and translinguistic connections. And I know German will be involved. It's tough to know how yet.

We will all keep our fingers crossed for that, Frances!