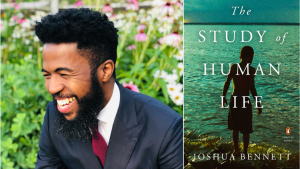

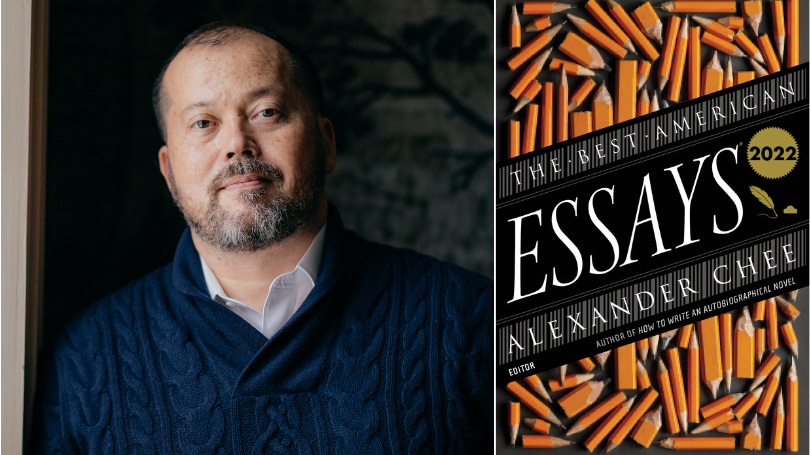

The acclaimed writer edited the newly released essay collection, which features the most diverse lineup of authors and publications in the history of the series.

When the celebrated writer Alexander Chee found out that he would be editing The Best American Essays 2022, he was still reeling from the COVID-19 pandemic.

"I had lost the ability to read books in the first year of COVID," Chee wrote in the collection's introduction. Describing his state of mind in January 2021, Chee says that he had also "lost faith in even the idea that writing might improve anything between people, but especially the idea that writing could or should teach empathy, or offer an education on biases to the enemies of an equitable multiracial liberal democracy—and that essays could do it."

Unexpectedly, Chee found that reviewing essay submissions for the book became a "recuperative act."

"The essays here are the essays that got me through the year," he says.

If sales are any indication, readers are seeking solace in the book too—just one week after its publication, the collection ranked No. 6 on the Indie Bestseller List for Trade Paperback Nonfiction Top Sellers.

An award-winning writer of both fiction and nonfiction, Chee is the author of two novels, Edinburgh and The Queen of the Night, and the essay collection How to Write An Autobiographical Novel. In its 2016 and 2019 editions, the Best American Essays featured Chee's work, which has also been published in numerous literary magazines. Among his many honors and awards, he was named a 2021 United States Artists Fellow and a 2021 Guggenheim Fellow in Nonfiction, and he is the recipient of a Whiting Award, an NEA Fellowship, the Randy Shilts Prize for Gay Nonfiction, the Paul Engle Prize, and the Lambda Editor's Choice Prize.

In a Q&A, Chee reflects on his selection process, the diverse lineup of authors and publications he settled on, and how most essays begin as "trifling ideas."

To prepare for editing The Best American Essays 2022, you went back to your favorite editions of the series from over the years to remind yourself of what you might be looking for. You note in your introduction that Anne Carson's "Kinds of Water" is an essay you've read every year for a decade. What is it that makes you return to an essay again and again?

That's probably a whole essay, answering that. In the case of that specific essay, each time I return to it, I have the feeling of encountering it anew, and feel the originality in the language, the narration, the metaphors, the structure, the pacing. Each time I read it I feel the world slough off, rinsed away, and I am deeply in the world of the essay. I study all aspects of the construction, listening to the prosody, thinking through the leaps in time, the logic of the story, the way it felt so casual even as it displayed so much rigor. It began as an education and became like an annual checkup of the mind.

Was the selection process more difficult than you anticipated?

I typically read a few essays every day for pleasure, about 1,000 a year. But I read many more than that for this volume. I knew I would be editing this in late 2020, and so I began reading for it before Bob Atwan, the series editor, sent me finalists. And while I knew I would be getting finalists from Bob, I still read the entire print runs of major literary magazines and some minor ones also.

As a college professor I have a budget for subscriptions, a dream. And so I subscribe to a wide range of publications, including The New Yorker, The Atlantic, Harper's, VQR, The Boston Review, n+1, The Paris Review, Granta, McSweeney's, The Washington Post, Freeman's, The Yale Review, The Asian American Literary Review, GQ, and Esquire.

I took something like 11 of the more than 200 essays Bob forwarded on to me, and found 12 on my own. Bob and I had many conversations over the decision period and sent many emails back and forth. I got my list down to about 30 essays after much agony, tried to talk the publisher into a longer volume, and got 23 instead of 20 essays.

The list of notable essays is 13 pages. I have a fantasy of a website with the notables all listed and hot-linked, but I would probably have to hire a few people and write a grant. Might be fun to do with students.

In his foreword Atwan points out that nearly every writer included appears in the series for the first time. There's diversity not just of writers but of publications. Was it a goal of yours to make this publication more inclusive than in years past?

I aimed to create a showcase of what I saw as the most exciting writing I found that year. But also, I think this is due in part to how I am when I put a list together.

If I could ever fault any previous Best American Essay editors, it would be for a focus on famous writers or the literary magazines everyone knows. I was thinking about those but also where we find essays now as readers. I love Roxane Gay's newsletter, for example, where Erika J. Simpson's essay appeared in a series Gay publishes of emerging writers. Kaitlyn Greenidge, also included, is a tremendous editor as well and edited Elissa Washuta's essay for Harper's Bazaar. Tanner Akoni Laguatan's essay first appeared at Wired, and I found it through Twitter. Wired and Harper's Bazaar both regularly publish work like this but they aren't known for it.

Bob is also part of this. He has a wide lens formally and in terms of subject matter, and many of the essays sent to me by him were like Brian Blanchfield's marvelous short essay on buying a home, published in an experimental online journal, or Jesus Quintero's "Anatomy of a Botched Assimilation," from another experimental online journal. Bob is a champion of the small magazines in his finalist suggestions, as well as someone interested in the essay as an art form.

But if you look back to previous curatorial projects of mine, like the writers series I created at the ACE Hotel, or for MailChimp at the Decatur Book Festival, you'll see that what looks like diversity is more of a push back against tokenization and an embrace of a fuller vision of the literature being published now.

Do you think that the pandemic prompted you to look especially for essays that provided a sense of escape?

It is clear to me now, in some way that it wasn't at the time, that I was after a recuperation of my love for writing and for the essay. Escape is something every reader hopes for. What was once so genteelly called "armchair travel" was reading something that absorbed you so thoroughly that your sense of time and place and self were rearranged. It's the original virtual reality. And I think if you're used to it, it becomes like a secular spiritual practice. Losing that during COVID was like losing a relationship to God if you were a lifelong believer. And I was—as a child I wandered into that church of the book we call a library and felt at home. So it wasn't escape I wanted; it was a return.

I needed to feel the awe I felt as I read Debra Gwartney on the house fire she and Barry Lopez so narrowly escaped; I needed to sit at a bar with Elissa Washuta, wondering what was next; I needed to swim the electronic lagoons of Azeroth in "World of Warcraft" with Tanner Akoni Laguatan. Or to ponder a gold chain with Justin Torres.

Did this process illuminate anything for you about creating a compelling essay?

I've known for a long time that you can write an essay about anything. A box of cigarettes someone spilled on the sidewalk and just left there. A strange pair of panties, not yours, mysteriously in your backyard. The water or lack thereof in your well. There's an essayist for The Guardian who proves this regularly, and he is beloved because nothing is too trivial for his notice.

Most essay ideas begin as trifling ideas. Perhaps I will write about Tiki drinks, the writer might say, sitting at night in a bar in Los Angeles, with one in front of them, and discover they are in fact writing about alienation, war, colonialism, and displacement.

I want to write about my grandmother instead, the writer might say, disappointed by the Tiki drink idea's confrontation with the self, and find themselves writing again about alienation, war, colonialism, and displacement. You might discover a connection between the Tiki drink and the grandmother and that the two ideas were one idea. Or you might realize you have a collection on your hands. In any case, all your little ideas are tricks that your big ideas are playing on you to get your attention.

In putting this collection together I followed the essays that I felt only that essayist could have written, the sort of essay that asserted the power of that writer to create the connections, juxtapositions, and observations that made connections I'd never seen before. Take Calvin Gimpelevich, for example, whose essay is about his realization that he was transitioning not just into becoming a man, but becoming a Jewish man, a part of a tradition he decided to educate himself on. Or Kaitlyn Greenidge, writing about the irony of finding her voice as an artist in a stage play she didn't realize was exploiting her as a young Black woman. How can an essay renew our idea of ourselves, each other, and the world? This is a question the form can answer differently every time, and that's why I love it.